The issues surrounding the billions raised to fight the deadly disease

As Americans learn more about cancer charity organizations and nonprofits, they often aren’t happy with what they find. Big salaries, suspicious distribution of funds and lack of results cause some to close the wallet. The controversy isn’t unwarranted, but a closer look at the issues reveals that not donating at all may not be the right choice.

Here are some common questions and their answers for those considering making donations to fight cancer.

When I Donate Money, Why Doesn’t All of It Go to the Cause?

Many cancer nonprofits have fallen under scrutiny for their skewed ratios of money raised versus money given to the cause. For example, recent reports from the Center for Investigative Reporting revealed a handful of charities that gave less than 10 percent of what they raised to cancer victims.

How could that be? In this particular investigation, it was discovered that these organizations paid millions of dollars to companies that solicit donations. In one case, $80 million was raised and almost $60 million went to solicitor fees.

A report in Bloomberg Markets Magazine showed that in 2010 the American Cancer Society (ACS) hired a company to gather donations. The company raised $5.3 million, but in the end that money only paid solicitor fees, and none of it went to cancer research. In fact, the ACS actually had to pay $113,000 in additional fees.

But those who donate should be comfortable with the idea that not all of the money they donate will be seen directly by cancer victims. Even good cancer charities must spend donations on fundraising efforts and administration. However, when a nonprofit is spending more than 35 cents to get a dollar, that can be a red flag.

Why Do Some Cancer Charity Leaders Get Six-Figure Salaries?

Seeing the salaries and benefits received by the leaders of many nonprofits is enough to keep some people from donating.

But the reason why nonprofits sometimes pay their leaders a lot is the same reason why for-profit businesses pay their leaders a lot, says Rick Cohen, Director of Communications and Operations at the National Council of Nonprofits.

“Nonprofits have to compete for top talent,” he says. “At the end of the day, for all organizations, you need to hire the right person.”

America’s best leaders often won’t take jobs without competitive salaries. The outrage some feel when seeing a big nonprofit salary most likely stems from a misunderstanding of the nonprofit sector. Nonprofit doesn’t mean everyone at the company volunteers. Nonprofits must pay what is often a host of full-time employees to keep the organization running. According to Cohen, 10 percent of the American workforce is in a nonprofit organization.

“The main difference between a nonprofit and a for-profit business is simply that a nonprofit is driven by a mission, and a for-profit is charged with increasing profit,” Cohen says.

All this said, sometimes salaries at cancer-related organizations are exorbitant. Cohen says that a good nonprofit will have performance and compensation reviews in place to keep leaders accountable. These reviews aren’t required, but potential donors can find out if a nonprofit is keeping leaders accountable through the websiteguidestar.org. Cohen says to look at what is called Form 990 for a nonprofit to understand leadership salaries.

“The best kind of donor is an educated donor,” he says. “Ask the organization for information and if they don’t give it to you, move on.”

What About Cancer Nonprofit Scams?

There are many organizations that have gotten rich off the kindness of others. It is the essence of despicable: create an organization with a legitimate-sounding name, create some deceptive marketing and throw in some accounting tricks, and you’re rich.

Take the Reynolds family, which created the Cancer Fund of America. The Center for Investigative Reporting found that over a span of three years the charity raised $110 million. Of that, $75 million was paid to solicitors, meaning people who went out and got money from people. Salaries within the company took more than $8 million in 2011 alone.

The organization gave misleading information about what they did with the money, or outright lied to donors. And it isn’t like nobody noticed. They’ve paid more than $500,000 to settle chargers, including the charge of lying to donors, but that is a small fraction of the money they were raking in.

Jim Reynolds Sr. used to work for the American Cancer Society, but after eight years was told to resign or be fired. The ACS accused him of sloppy bookkeeping, irregular hours and taking a car meant to be auctioned for charity. That’s when Reynolds started his own charity, basically rewording the name of the organization he previously worked for. He sent out volunteers to collect and they raised millions in the first year.

Little of the money was used for direct financial aid to cancer patients. Reynolds got businesses to donate things, then he repackaged them and gave them to cancer patients. Meanwhile the money went to the professional fundraising organizations and salaries for his extended family. Overall, in a decade, cancer patients received $890,000, along with some donated items like shampoo, paper plates and toys. Reynolds family members received $5 million. Solicitors received $80 million.

The Cancer Fund of America was rated the second worst charity in America by the Center for Investigative Reporting.

Stories like this are enraging, and unfortunately lead to people giving less, understandably.

“One shady character harms the efforts of other nonprofits,” Cohen says, “even though the overwhelming majority of nonprofits are making a difference in their communities.”

Part of the reason why these few unsavory characters are able to do so much damage to the cancer nonprofit world is because the IRS has a hard time enforcing regulations in the nonprofit sector, Cohen says.

“The IRS department that deals with nonprofits is under-funded and under-staffed,” he says. “We need congress to fund the IRS to enforce regulations.”

But, Cohen says, the dishonest nonprofits make up a minuscule percentage of all the nonprofits, even though the media exposure might make it seem otherwise.

“There are true heroes working all across the U.S.,” he says.

Deciding not to give at all because of families like the Reynolds might be a rash decision. Surveys show that nonprofits struggle to keep up with demand, and that demand is always increasing. In other words, most nonprofits could help more people if they had more donations.

In fact, the American Cancer Society can’t fund 90 percent of the research that is submitted and deemed worthy of funding, according to Otis Brawley, MD, chief medical officer of the ACS.

How Can I Know If a Charity Is Worth Donating To?

Many cancer charities aren’t out to take advantage of people, but are simply run badly. Just because a nonprofit has a great goal doesn’t mean they are a good organization to donate to.

An example of a good cancer charity is the Entertainment Industry Foundation (EIF), which organized Stand Up To Cancer and many other events. They received a 91 out of 100 on Charity Navigator, a respected watchdog of the charity sector. Of the $50 million they raised in 2012, 78 percent went to the programs and services it was designed to provide. The rest went to salaries and fundraising. While some might look at the remaining 22 percent and cry fraud, this is actual a great ratio. It takes a lot of money to make a lot of money, even in the nonprofit world.

For sake of comparison, let’s take a look at the American Cancer Society, which also has a bunch of big events throughout the country each year.

They raised more than $880 million in 2012. Of that, $60 million went to administrative expenses, and almost $340 million went to fundraising expenses. That left $586 million, or 59 percent of the money raised to go towards the many different areas of cancer research and assistance.

Charity Navigator gives the ACS, a prestigious cancer organization, a 76 out of 100 score.

So is the ACS bad and the EIF good? Rick Cohen says expenditure numbers aren’t a complete and accurate measure of nonprofits, and that potential donors shouldn’t shun organizations just because administrative costs are high.

“Costs can vary from year to year,” he says. “New equipment, new initiatives and other things can make administrative expenses seem high, but in fact they are making the nonprofit better.”

Charity Navigator and GuideStar are great tools for donors to learn more about organizations. Become an educated donor.

What Exactly Is My Money Going to Do?

Donors have a right to know what their money will do, but the responsibility to gain that knowledge is largely on their shoulders. Some nonprofits work to make life better for cancer patients. Other nonprofits work to fund research institutions working to find cures and better treatments. Put your money where you want.A related question some may ask is this: “will my donation actually do anything?”

What have the billions donated to cancer actually achieved so far? And why is it taking billions of dollars?

Let’s take a trip back to the 70s. President Nixon signed the National Cancer Act in 1971. Government funding started flowing into the fight against cancer at that time, and public attention grew.

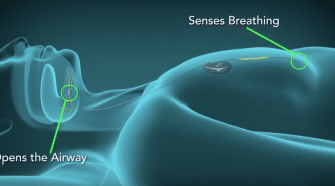

Researchers today realize that our understanding of cancer in 1970 was weak, to say the least. We used to think cancer was a single disease, but we now know cancer to actually be more like 200 distinct diseases, with different causes and requiring different treatments. This has opened the door to treatments, survival and cures.

Taxes and Cancer

You pay taxes? You’re so charitable! In 2013 Congress gave the National Institutes of Health $5.27 billion to put toward cancer research. Source: report.nih.gov

Cures? Yes! Thanks to years of clinical trials and medical research, testicular cancer can be cured in the vast majority of men, especially if detected early. Hodgkin lymphoma, which used to be fatal, is now routinely cured, thanks to clinical research.

Survival rates in common cancers have improved drastically. Death rates from cancer dropped 22 percent for men and 14 percent for women from 1990 to 2007, according to a report from the American Association for Cancer Research. Among children, 80 percent can expect to survive childhood cancer now, compared to 52 percent in 1975. Today there are more than 14 million living cancer survivors, compared to just 1.5 million in 1970, according to John Sweetenham, MD, Executive Medical Director at Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI).

“There have been extraordinary advances,” he says.

One incredible area of cancer research is the Human Genome Project, which is continually discovering genetic drivers of cancer. Specifically, the Cancer Genome Atlas is searching for what gene changes cause a cell to become cancerous. This research is especially important for identifying specific sub-types of cancer, which means treatment can be more specific. There now exist dozens of FDA-approved targeted cancer drugs.

Sweetenham says cancer research is so expensive in part because it is so labor intensive.

“A very large component of cancer research is the expertise, the people,” he says.

Researchers in labs make discoveries, other researchers try to develop treatments from those discoveries and still more experts must navigate the appropriately stringent FDA regulations for new medications.

“It requires a lot of people in different areas of expertise,” he says. “It requires an infrastructure.”

The government helps support this research. In 2013 Congress gave the National Institutes of Health $5.27 billion for cancer research. But progress still depends heavily on nonprofits.

“If non-National Cancer Institute funding went away tomorrow, it would have an enormous impact on what we are able to do,” Sweetenham says.

Cancer nonprofits do gather quite a chunk of change, but it is very little compared to the money cancer takes from America every year. Sweetenham says that in 2012, cancer cost the U.S. between $200 and $220 billion, in cancer care and economy impact.

Even with all the progress, we’re losing too many people every year to cancer. It is without a doubt worth donating for.

Which Cancer Should I Donate To?

This is largely a personal decision, based on your experience with cancer.

Those not swayed by personal experience may wonder if breast cancer and prostate cancer are the most important cancers to donate to. Organizations that fight these cancers have great marketing and awareness campaigns, leading to these cancers getting the most monetary donations every year. But these aren’t the cancers that kill the most people.

Lung cancer is the biggest killer. So why don’t more people donate toward that cause? Lung cancer is unique in that smoking is a known cause, therefore sympathy isn’t as great for lung cancer victims compared to other cancer victims. But lifestyle factors play into about half of all cancer deaths, according to the American Association for Cancer Research, so it is illogical to base donations on culpability. The truth is that survival rates for lung cancer haven’t improved nearly as much as they have for other cancers, and more donations would do good.

But just because you don’t donate to lung cancer doesn’t mean you won’t help that science. Discoveries with one cancer often apply to others, according to Sweetenham.

“What we often find is that mechanisms at work in one cancer are relevant in others,” he says.

In multiple instances, cancer drugs have failed for the cancer they initially target, but are found to improve outcomes in other cancers. A drug called cisplatin was developed as a treatment for testicular cancer, and now it is the most commonly used chemotherapy for lung and ovarian cancer.

Remember, however, that just because an organization markets well doesn’t mean their cause is more important than others.

Sources: ascopost.com, healthland.time.com, charitynavigator.org

No Comment