Written by Daniel G. Amen, M.D.

Physicians have been trying to drug the brain into submission since the 1950s. The outcomes have been poor because doctors too often ignore the necessity of first putting the brain into a healing environment by addressing issues such as sleep, toxins, diet, exercise, and supplementation. Dr. Thomas Insel, former director of the National Institute of Mental Health, wrote, “The unfortunate reality is that current medications help too few people to get better and very few people to get well.”

In contrast with antibiotics, which can cure infections, none of the medications for the mind cure anything. They only provide a temporary bandage that comes off when the psychotropic medications are stopped, causing symptoms to recur. In addition, many of these medications are insidious; once you start on them, they change your brain chemistry so you need them in order to feel normal.

Honestly, I undervalued brain health for nearly a decade as a young psychiatrist until our group at Amen Clinics found a practical way to look at the brain. Before we started our brain imaging work in 1991, I had been trained and board-certified as a child-and-adolescent psychiatrist and general psychiatrist and was busy seeing children, teens, adults, and older adults with a wide variety of issues connected with mental health, including depression, bipolar disorder, autism, violence, marital conflict, school failure, and ADHD. During that time, I was flying blind and not thinking much about the actual physical functioning of my patients’ brains. Researchers at academic centers told us that brain imaging tools were not ready for clinical practice—maybe someday in the future.

I loved being a psychiatrist, but I knew we were missing important puzzle pieces. Psychiatry was, and unfortunately remains, a soft, ambiguous science, with many competing theories about what causes the troubles our patients experience. In medical school and during my psychiatric residency and child- and-adolescent psychiatry fellowship, I was taught that while we really didn’t know what caused psychiatric illnesses, they were likely the result of a combination of factors, including genetics, abnormal brain chemistry, toxic parenting or painful childhood experiences, and negative thinking patterns.

“The unfortunate reality is that current medications help too few people to get better and very few people to get well.”

-Dr. Thomas Insel, former director of the National Institute of Mental Health

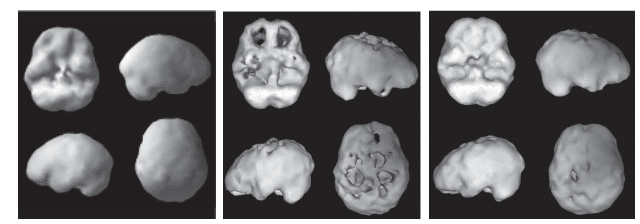

IMAGING CHANGED EVERYTHING

My lack of respect for the brain vanished almost instantly when I started looking at the brains of my patients with a nuclear medicine study called Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT). It is different from CT or MRI scans, which look at the brain’s anatomy or structure. SPECT looks at brain function, which is helpful because functional problems almost always precede structural problems. SPECT is a leading indicator of trouble, pointing to issues years before they manifest, while CT and MRI are lagging indicators of trouble that reveal abnormalities later in illnesses. SPECT answers a key question about each area of the brain: Is it healthy, underactive, or overactive? Based on what we see, we can stimulate the underactive areas or calm the overactive ones with supplements, medicines, electrical therapies, or other treatments, all of which optimize the brain. We can also help patients ensure that the healthy areas of their brains stay healthy.

Almost immediately after starting to look at scans, I became excited about the possibilities of SPECT to help my patients, my family, and myself. The scans helped me be a better doctor, as I could observe the brain function of my patients. I could see if their brains were healthy, which meant the issues they were facing were more likely to be psychological, social, or spiritual rather than biological in nature. I could see if there was physical trauma from concussions or head injuries, causing trouble to specific areas of the brain, or if there was evidence of toxic exposure from drug or alcohol abuse or other toxins, such as mercury, lead, or mold. I also could see if my patients’ brains worked too hard, which is associated with anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive tendencies.

Now, close to 30 years after we started to look at the brain at Amen Clinics, we have built the world’s largest database of nearly 150,000 brain SPECT scans on patients from 120 countries.

No Comment